"With Affectionate Good Will"

Every time you purchase a used book, you also buy a mystery.

The cover show, as the dealer described, its shelfwear and “moderate tanning along edges.”

Like the cat with the proverbial nine lives, each book has a story to tell, if you could only rummage around and—with luck—find its hidden history. Who owned this book before you? How many owners have there been? Where did they live and how did the book travel from one place to the next?

Was it a favorite of a particular owner, who nodded off at night with the open book on their lap? Was it used for research or was its purpose not so much to inform as to entertain? Or did it languish on a shelf unread, its secrets yet to be discovered?

Most of the time we can never answer these questions that come with an old book. But every once in a while, a little volume falls into your hands and you can gain a glimpse of its previous lives.

Settle back. That’s the story you’re going to hear today.

The book’s title page.

For many years I have collected signed copies of Starrett’s best book of poetry, Autolycus in Limbo. Published in 1943 by E.P. Dutton and Company of New York, it has many little points to recommend it.

For example, the title is a reference to an obscure Shakespearan character from “The Winter’s Tale.” His name no doubt came from an equally obscure character from Greek mythology. Starrett described Autolycus as “a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles.” That was his way of undervaluing his own poetic observations.

But as Sherlockians know, “there is nothing so important as trifles.”

The book is dedicated to Starrett’s two favorite aunts, Lilian and Bella Starrett with “All Love and Gratitude.” They were vitally important people in Starrett’s young life.

After Starrett’s parents moved from Toronto to Chicago when he was 4, he would go back to stay with them every summer for the next 10 years. Their musty attic was a treasure house where he explored the hundreds of books his aunts read and never tossed out.

Starrett’s dedication of Autolycus in Limbo.

It was in this pile of books that he first pulled out a copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and spent the entire afternoon entranced. His life was never the same afterwards..

So much for the book in general. Let us get down to specifics for this particular volume.

Copies of Autolycus in Limbo are quite common, and Starrett must have signed many of them over the decades. So when one came up for sale at a very good price, I checked it out. Here is how the dealer listed the book:

The dealer’s description of his copy of Autolycus in Limbo. I’ve blanked out information which could identify the dealer.

Notice the dealer did not include the name of the person to whom Starrett inscribed the volume. That’s not uncommon. The price was a very friendly $35. So I paid it and 10 or so days later the book made its way to my mailbox. After unwrapping it, I flipped it open to the front free endpaper and saw this.

I goggled.

I sputtered.

Words which I cannot print here came from my lips.

Could this be real?

After spending some time with it, I can say yes. It’s real. And it’s here in front of me as I type. For $35 plus postage, I managed to stumble on a true piece of Sherlockian/Irregular/film/radio history.

Why do I think it’s real? It is a reasonable question. Starrett signatures have been called into question, so it is worth a few moments of discussion.

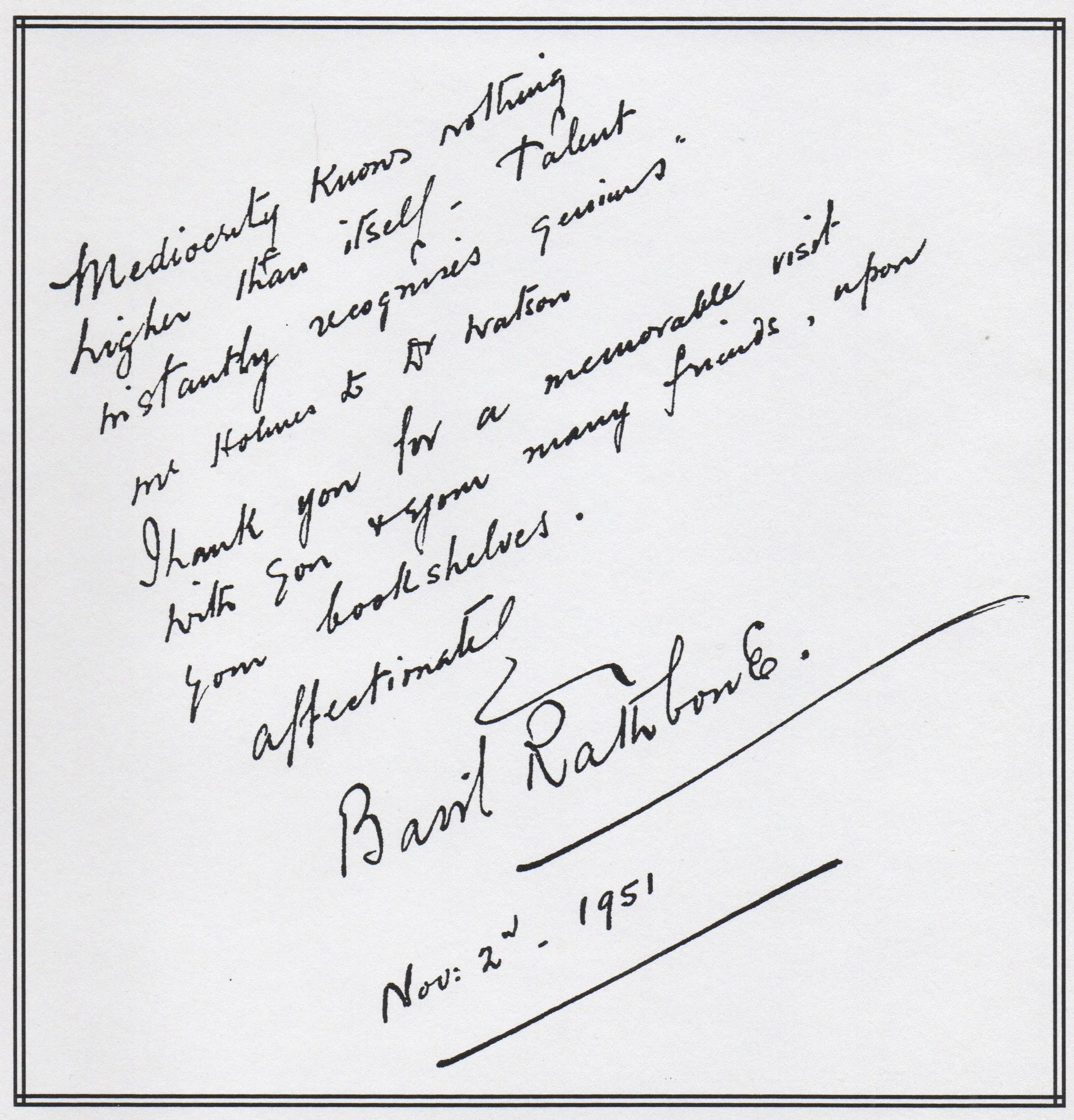

In addition to certainly being in Vincent’s handwriting, we know that Starrett and Rathbone were together at Starrett’s Chicago apartment on November 2, 1951. For decades, the Starretts kept a guest book, starting from their time in China in the 1930s through the 1960s. Friends were asked to sign it and we are fortunate that Rathbone decided to do so. That guest book is now part of the Starrett collection at the University of Minnesota’s Elmer L. Andersen Library.

In 1990, BSI member Bruce Southworth had the relevant page reproduced and included in the dinner packets for the Baker Street Irregulars, as you can see here.

To further seal the deal on its authenticity, we have Starrett’s own words about that evening.

In an August 10, 1969, column for the Chicago Tribune, Starrett recalled Rathbone’s visit and remembered:

He took with him a copy of one of my sonnets, which he later included in his recordings and read many times in his one-man shows, ‘An Evening with Basil Rathbone.’

After getting through the initial shock of the inscription and discovering the earlier owner of the book, I started thumbing through this copy of Autolycus.

“221B” as it appears in most copies of Autolycus.

I had hoped that Rathbone might have made a notation somewhere, since the dealer remarked that the book held “a few notes in pencil.” I found the notes but there was none that seemed to come from Rathbone’s pencil.

Indeed, from the perspective of a Sherlockian, there was nothing remarkable about the book until you got to the most important page, the one that prints “221B”.

Here’s how that page looks in every other copy of Autolycus that I’ve ever seen. As you can see, it is the 32nd poem in the book.

However, when you reach the corresponding page in Rathbone’s copy, there is a surprise.

The replacement page for “221B” in Rathbone’s copy of Autolycus.

The original page is missing!

In its place is this photocopy from another version of what is called “221:B”.

I don’t know what happened to the original page, but I can speculate.

In the 1950s, Rathbone and his wife, Ouida, cobbled together a Sherlock Holmes play. Rathbone asked Starrett to consult on the project. We have some of their correspondence during this period, and we know that Rathbone planned to read “221B” before the curtain was raised on the play, to help set the mood for the evening. Starrett loved the idea and gave it his blessing.

The play was, to put it mildly, a disaster from rehearsals onwards. Starrett learned that during rehearsals, Rathbone did not recite the poem, but that someone else did. Starrett sent a telegram to Rathbone about this, a copy of which is in the Andersen Library.

Starrett’s telegram protesting the way in which his poem was used before the curtain was raised during rehearsals of Rathbone’s play.

This might explain why the page is missing. Rathbone could have cut out the poem from the book to use for the play. It is possible he had a photocopy of another version of the page made and inserted into the book. However, photocopies were expensive in the 50s and machines were not to be found in every library and office as is the case today.

In any case, the insertion into the book was done with care. Indeed, I’ve shown the book to a few bookmen, and they agree it is a professional job, perhaps done by a professional book binder. Would Rathbone have gone through this type of effort and expense? It is hard to say.

By the way, I’m not sure where this version came from. If anyone recognizes where this printed version of “221B” originated, please let me know. That colon between 221 and B is distinctive.

While the play closed after 3 performances, the friendship between the actor and the poet continued, largely through correspondence. And, as I have noted elsewhere, “221B” continued to play a large part of that relationship.

At some point after Basil Rathbone owned this inscribed copy of Autolycus in Limbo, it came into the collection of the head of the of the YMCA in Redwood City, California, Orval G. Graves. We know this because Graves glued a bookplate into the front paste-down endpaper of the book, opposite Starrett’s inscription to Rathbone.

The bookplate is a handsome image of a pine sapling, and is based on work by the American artist Rockwell Kent. The bookplate is stamped with the following information:

Orval G. Graves

503 Flynn Avenue

Redwood City, Calif, 94063

A photo of Orval C. Graves from Dr. Richard C. Rutter’s chapbook, Knights of the Gnomon: Redwood City, California Scion of the Baker Street Irregulars of New York, An Introductory Handbook,

We know that Graves had a deep interest in Sherlock Holmes. According to a story in The Peninsula Times Tribune of Palo Alto, Calif. for June 17, 1984, Graves taught a seminar in Sherlock Holmes in 1978 at Canada College in Redwood City. The students liked the seminar so much they agreed to keep meeting.

Thus was born the Knights of the Gnomon, a scion society of the Baker Street Irregulars. The scion continues to this day and its history and rituals were recorded in 1991 by Dr. Richard R. Rutter in Knights of the Gnomon: Redwood City, California Scion of the Baker Street Irregulars of New York, An Introductory Handbook.

This is speculation, but I believe that it was Graves who had the photocopied version of “221B” placed into the book where the original page once existed. Photocopies were less common in the 50s when Rathbone owned the book, but were becoming more available and affordable after his death in 1967. We don’t know when Graves bought the book, but he may have purchased it after Rathbone’s death and owned it in the 70s and 80s when photcopying was widely available.

That Graves held “221B” in high regard is also very likely.

According to Rutter’s history of the Gnomon, “Meetings are opened with a reading by the evening’s host of Vincent Starrett’s “221b”

This is followed by a reference to Appendix item No. VIII. If you flip back to that reference number, you will find this handsome illustration awaiting you.

So there you have it. A few mysteries solved, several possible lines of speculation laid out and (I hope) a fine evening’s entertainment provided for you all.

My thanks to Marsha Pollak, Steven Rothman, Peter Blau and those others who guided me on my research.

Cheers!