The Great Hiatus, 1934-1960

Private Life Chapter 7: In which a lot happens without a new Private Life

A chapter in this 1938 book of Starrett’s essays included “Sherlock and After,” a rumination on the future of the detective story.

Let’s pause for a minute and summarize.

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was published in the United States (1933) and London (1934) to largely positive reviews. The response was so good in the U.S. that a second printing was ordered.

With Private Life, Starrett hoped he had written a classic, a book that would be every bit as popular as the Holmes stories themselves. And while the book certainly had some success, it slowly slipped from the shelves and demand faded. This was, after all, the height of the Great Depression, a time when paying the rent and putting food on the table was a daily challenge for many, and books were an unthinkable luxury for most.

Starrett went back to writing mystery novels and short stories, was named president of the Society of Midland Authors, edited a book of Stephen Crane works for the Modern Library and continued to add to his mighty book collections.

The Starrett-Morley Connection

For the most part, Starrett set Holmes aside.

But then a curious thing happened. Christopher Morley, a New York writer, sent a letter to Starrett praising Private Life. The two had a desultory correspondence before, but Holmes gave them a common bond.

The friendship is in so many ways improbable. They were very different men.

Morley was a Haverford undergraduate, Rhodes scholar and classically educated writer. Starrett didn't finish high school and was a self-educated polymath. The most time he spent at a college was teaching journalism for one semester as an adjunct.

Morley went to study modern history at New College, Oxford on his Rhodes scholarship. To get to England, the young Starrett worked as a hand on a cattle ship literally mucking out stalls. He was so poor when he got to London he had to beg for food money.

Nonetheless, Morley and Starrett became fast friends, which shows the power of Sherlock Holmes to build bridges. They shared a love of poetry and prose, good books, tobacco and decent booze. Their close friendship—sparked by Private Life and made fast by their shared love of Sherlock Holmes—remained strong for the better part of three decades, until Morley's death in 1957.

In this way, their friendship foreshadowed the lifelong friendships many of us share.

Adding Edgar W. Smith

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was instrumental in bringing others from around the country into what was the beginnings of the Sherlock Holmes movement.

Besides the Morley connection, the most important link was no doubt that of a Vice President at General Motors named Edgar W. Smith. Smith wrote to Starrett to compliment him about the book, and then began picking apart some of Starrett's theories in favor of his own.

Starrett told Smith to look up Morley, and the troika was complete. These three men would be the heart and soul of the Sherlock Holmes movement in this country for 30 years. They are our Sherlockian forefathers, and we owe them a great deal.

Woollcott's anthology, Long, Long Ago reprints his "Shouts and Murmurs" column from The New Yorker on the Baker Street Irregulars 1934 dinner.

Back to the 1930s. Morley was so excited about Starrett’s book that in 1934 he invited the Chicago writer to New York to attend the first official meeting of a group Morley called The Baker Street Irregulars. Starrett loved the trip East, got into hot water with Morley for inviting Alexander Woollcott, but had a wonderful time among the Irregulars, as you can tell from his account.

He would be invited back for the rest of his life, but this was the only time he would attend a BSI dinner. There were several reasons: He was perpetually broke, and he often had pressing deadlines, but the biggest reason was the emotional instability of his girlfriend and, later, wife, Rachel Latimer. While he still made occasional trips out of the city, Starrett’s life now revolved around Chicago.

Starrett found plenty to keep him connected with the world of Sherlock while in Chicago, where he was (rightly) often referred to as “the dean of Chicago Sherlockians” and “the man who knows more about Sherlock Holmes than anyone else.”

A few highlights of his Sherlockian career:

1934: His essay, “The Singular Adventures of Martha Hudson” was included in the anthology, Baker Street Studies edited by H.W. Bell. This essay is very much in the spirit of those he had already written and would play a role in a later edition of Private Life.

Baker Street Studies would become a classic of the genre, and it’s easy to see why. Starrett found himself between covers with Dorothy L. Sayers, H.W. Bell, S.C. Roberts, Ronald A. Knox and several other respected commentators whose work we continue to read today. Not bad company for the boy who didn’t finish high school.

The dust jacket to 221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes, edited by Starrett.

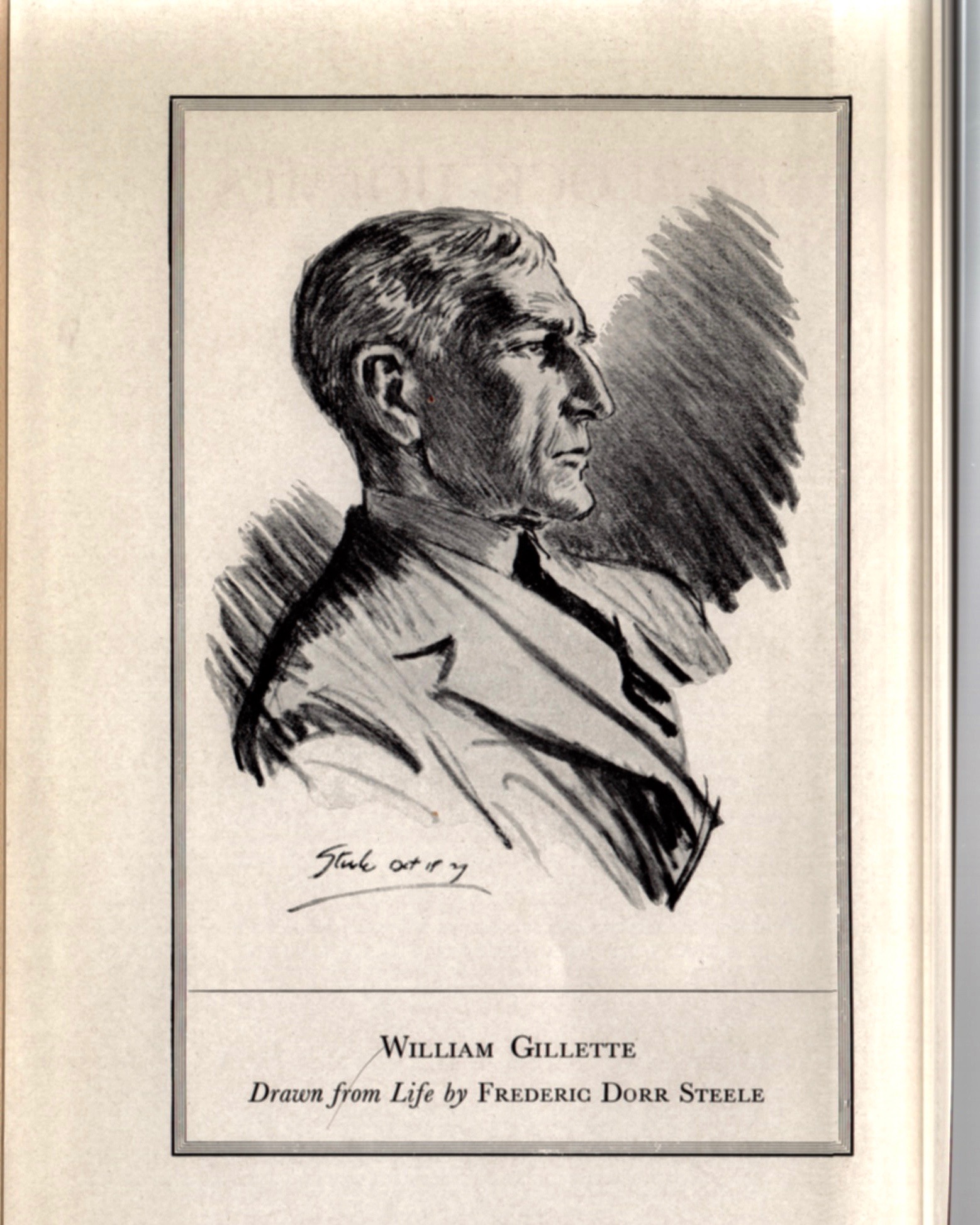

1935: Starrett edited Sherlock Holmes: A Play, the William Gillette production that had taken New York and London by storm at the turn of the century. Gillette and Starrett had met before and were corresponding friends before being reacquainted at the 1934 BSI dinner.

“It is as the living embodiment of Sherlock Homes that he will go down the happy boulevards of time. It is not a bad fate,” says Starrett in his introduction. The book would get a second life in 1974 after the Royal Shakespeare Company produced the play to great acclaim.

(Illustrations from the book are above.)1938: “Sherlock and After” is one of the essays in Persons from Porlock. It’s a speculation on the future of the detective/mystery story and suggests that the days of the brilliant amateur are over with the advent of the hard-boiled school. Holmes is often mentioned.

1940: Starrett edits 221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes, an anthology of Sherlockiana, published by Macmillan, the same publisher of Private Life. Starrett contributes his own “The Adventure of the Unique Hamlet,” originally published 1920.

“Only those things the heart believes are true.”

The first book printing of Starrett's immortal poem "221B."

1942: On March 11, Starrett pens what would become the most popular poem in the Sherlock Holmes movement: “221B.” You can read more about the poem’s history here.

The same year, Starrett had become a regular book columnist writing “Books Alive.” The column started in the Chicago Daily News and quickly shifted to the Chicago Tribune, where it was a fixture for the better part of three decades.

One of his first columns dealt with the discovery of a “new” Sherlock Holmes story purportedly by Conan Doyle, but later proven to be by another author.

The dust jacket for Edgar Smith's anthology. Starrett contributed two poems and an essay on Mrs. Hudson, all reprinted from earlier publications.

1943: The Hounds of the Baskerville (sic) was created by Starrett and three like-minded men. It was the first of the Chicago Sherlockian societies and has just celebrated its 76th anniversary.

1944: Starrett has three contributions in Profile by Gaslight: An Irregular Reader about The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. (Notice how Edgar worked Starrett’s title into this book’s subtitle.)

All of Starrett’s contributions are reprints of earlier items: two poems, "221B" and "To A Very Literary Lady"; and the essay "The Singular Adventures of Martha Hudson” from Baker Street Studies (see above.)1955: Starrett would be teamed once again with a William Gillette script when he wrote the brief introduction to The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes: A Fantasy in One Act. Ben Abramson, who had been the first publisher of the Baker Street Journal, produced a little booklet of the curtain raiser Gillette originally subtitled: “A fantasy in about one-tenth of an act.”

Hard Times

Title page to The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes. Starrett contributed a forward.

By the late 1950s, Starrett’s fortunes started to decline.

He had written a biography of 750 pages but could not find a publisher. His earlier career as a mystery/detective writer was long gone, overcome by more modern tastes. Even his column in the Tribune was starting to seem stuffy and quaint, a holdover from an age before television and films were the chief ways Americans found their entertainment.

In 1960, Starrett would turn 74. He and his wife were suffering the hardships of their advancing age. More importantly, they were living hand to mouth. Having failed to build a nest egg for their senior years, and with Medicare still 5 years in the future, something needed to be done to bring in badly needed cash.

Starrett once again turned to Sherlock Holmes.