A Bookman and his Dealer

To a collector, his dealer is both his ally and his temptress. Ben Abramson was that and more for Vincent Starrett.

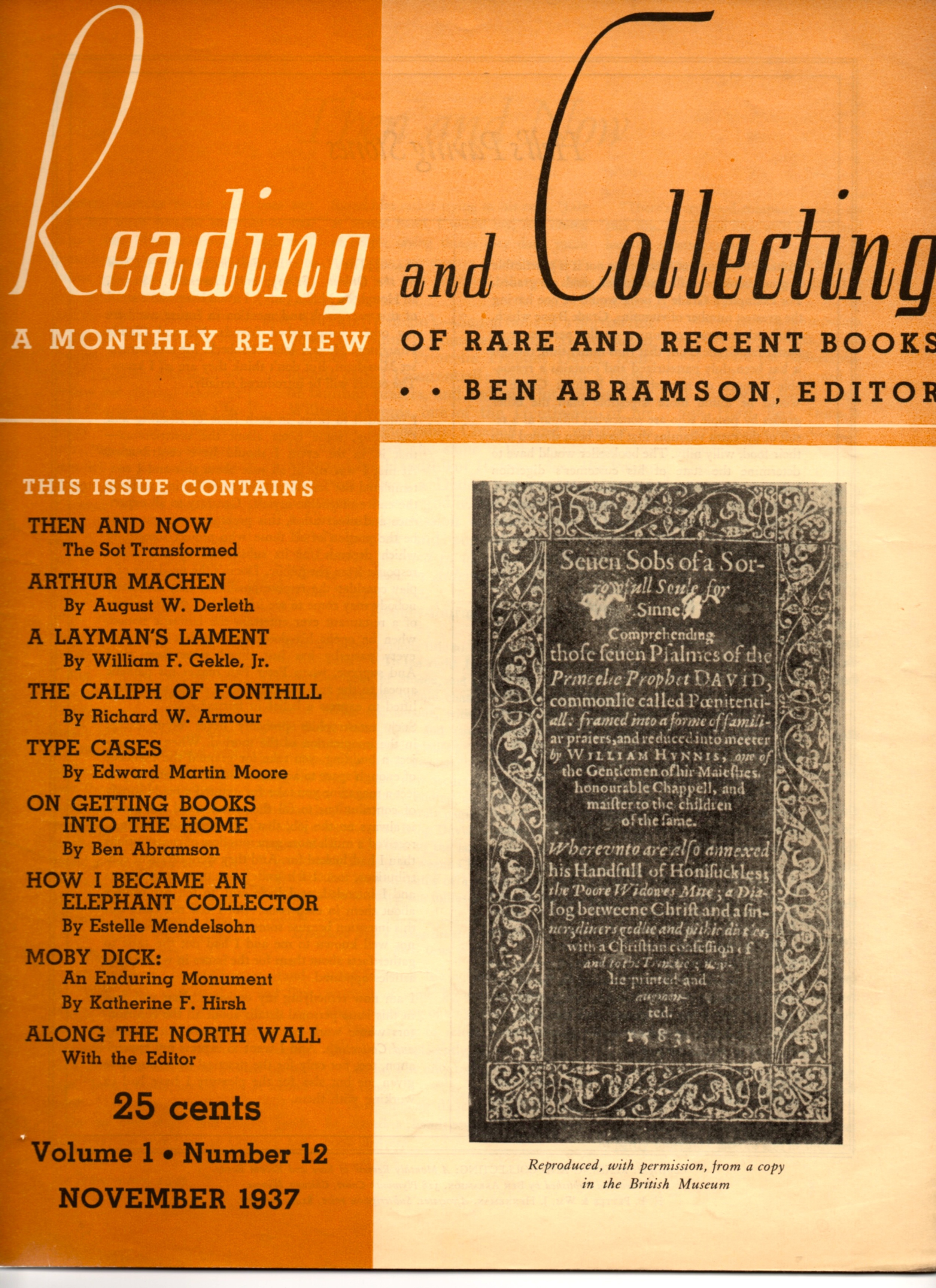

Starrett's article got top billing in the list on the left. Sadly, this was the last issue of Reading and Collecting.

Several months back I sat down to lunch with Baker Street Journal editor Steve Rothman and he pulled out a large envelope and said, “You might enjoy this.”

I did indeed.

Upon such generous gifts are little literary expeditions founded.

Inside that envelope was the last issue of Ben Abramson’s lavish newsletter Reading and Collecting, devoted to authors, books and book collecting. This number was dated February-March 1938 and its lead article was “On a Desert Island” by Vincent Starrett.

The article is a fantasy dialogue between Starrett and his dear —and imaginary—Great-Aunt Matilda who have washed up on a desert island. (See note No. 1 at “The More You Know” at the end of this essay for more on Aunt Matilda.)

To while away the time, the two attempt to put together a list of books they wished they had saved from the ship’s library, but quickly get into one spat after another. She chides him on his inability to be selective. Spying a sail on the horizon and wearying of his chatter, Starrett’s aunt begins teasing him by calling him “a man of letters.” Starrett becomes enraged and demands to know what she means.

“Mr. Christopher Morley,” replied my great-aunt exhaustively.

Plunging boldly into the tide, she struck out with long slow strokes for the horizon. Out…and out…and out…

The Dealer

Reading and Collecting was a later venture of Ben Abramson, whose first business was book selling. Abramson and Starrett got to know one another when Abramson opened his first Chicago bookshop with Jerold Nedwick on Wabash Avenue near Congress Street. Recalls Starrett in Born in a Bookshop:

“Small and dark as was their first establishment, some attractive finds were made there, and some of the choicer spirits of the ‘renascence’—among them Lee Masters—were frequently to be seen among the researchers.”

Nedwick and Abramson ended their business partnership, and Abramson went on to establish his own shop, “the famous Argus Book Shop, with wide rooms overlooking the lake in Michigan Avenue, where on good days one might encounter such visiting celebrities as Christopher Morley and Somerset Maugham,” recalled Starrett.

It was at his shop at 333 South Dearborn Street in Chicago that Abramson came up with the idea for his monthly magazine of rare and recent books, Reading and Collecting. The magazine grew out of his regular book catalogues and his column, “Along the North Wall.”

Abramson set out his vision for his new magazine in the first (December 1936) number’s lead editorial:

“Frankly, I want to expand my audience, to spread my enthusiasm about certain books to a wider radius. I want to extend the knowledge of book collectors about the books they collect, both on the material and the literary side. I want to tell collector facts that will interest them about the book they hold in their hands and the book the read. I want to talk about writer and their experiences about books and their history. About typography, binding, illustrating, publishing, collecting, and selling I want to establish an intimate relationship between collectors and those who have produced the books they collect.”

In the next 15 issues, Abramson made good on his goal.

“Every number, as I beheld it fresh from the printer, oozed courage and enthusiasm. My friends and customer were likewise enthusiastic. Unsolicited articles poured in steadily—as I expected. My subscription list was building up—as I expected. I got letters of praise and criticism—as I expected. The magazine was even better than I expected.”

Reading and Collecting and Sherlockians

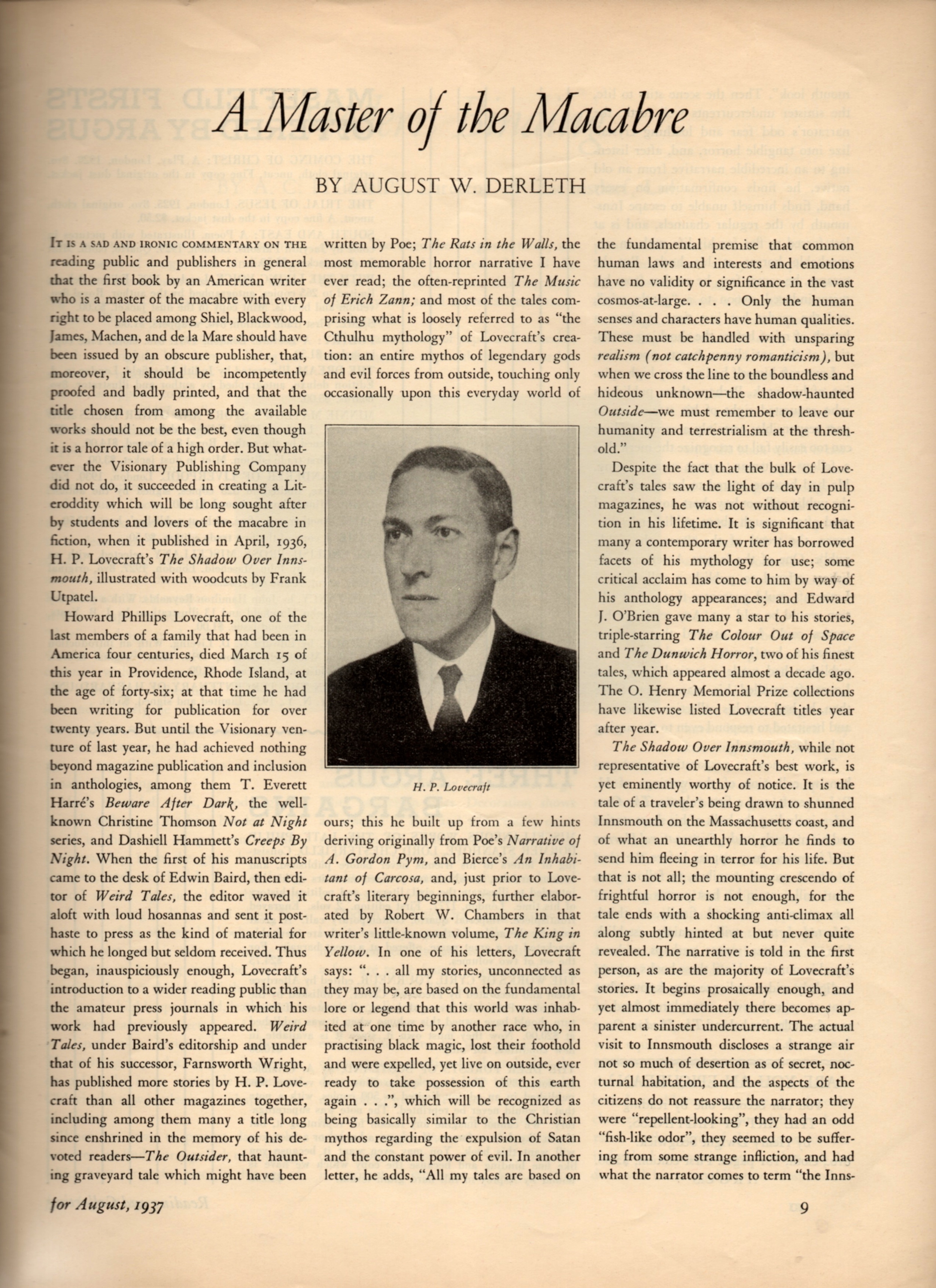

Scattered amongst the pages of Reading and Collecting are the names of those who would be influential in the Sherlock Holmes movement of the 1930s and 40s. August Derleth (“Inspector Baynes, of the Surrey Constabulary”) offered two articles: one each on H.P. Lovecraft and Arthur Machen (one of Starrett’s favorite authors). P.M. Stone (“The Speckled Band”) had a three-part series on contemporary detective fiction.

And James Keddie, co-founder of the Speckled Band of Boston, offered a elegant fantasy on the death of J.M. Barrie, imagining his last fevered vision of Tinker Bell, come to spirit him away to a land where no one grows up or dies.

There was lots of stuff by and about Christopher Morley. The BSI’s progenitor offered a poem, “Chicago,” and a bit of Shakespearean whimsy, entitled “Lines Found in the First Tomfolio at Stratford-On-Avon.” Morley shows up often in Abramson’s various columns and for good reason: Morley’s books Old Loopy: A Love Letter for Chicago and Notes on Bermuda were published by Abramson.

Abramson himself would be invested into the Baker Street Irregulars as “The Beryl Coronet” in 1949. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

As I said, Starrett’s desert island fantasy came in the last issue of Abramson’s magazine. While he had great interest from authors and collectors, Abramson failed to find advertisers for Reading and Collecting. And without advertisers, the enterprise folded.

“Expenses were alarming. They not only exceeded the proceeds of the magazine and my own advertising, but they exceeded the profits of the book business.”

It was a story that would be repeated a decade later with The Baker Street Journal.

Starrett and Abramson: Their later years

In 1944, Abramson moved to New York and started a new Argus Book Shop at 3 West 46th Street. Three years later, the first issue of The Baker Street Journal appeared, with Edgar W. Smith as its editor. Starrett was listed as Honorary Associate Editor, and had a brief article in that first issue “Calix Meus Inerbrians Quam Praeclarus Est.” (See note No. 2.)

The back cover of the issue features real and “faux” advertisements, including one for Books and Bipeds, one of Starrett’s last compilations of essays, largely drawn from his Chicago Tribune “Books Alive” column. Books and Bipeds was published by Abramson in 1947.

Abramson’s affection for the work is obvious, and the dust jacket blurb for Books and Bipeds echoes the publisher’s own interests, “Books and Bipeds is a commentary on the world of books and bookmen, on adventures in the world of literature and on life as it is reflected in books.”

Returning to the BSJ's back cover, adjacent to the ad for Books and Bipeds is one for Reading and Collecting, offering all 15 issues for just $10. (See note No. 3.)

The next issue of the BSJ would offer the same ad for Books and Bipeds, plus one for two other of Starrett’s works: Autolycus in Limbo and Snow for Christmas.

Unfortunately, Abramson’s enthusiasm for the BSJ was not enough to keep it going. He had printed far too many and was stuck with stacks of unsold copies. The Journal lasted 13 issues in what would become known as the Old Series — just two issues shy of Reading and Collecting's full run.

But a bigger problem loomed for Abramson. His health was deteriorating as rapidly as his financial fortunes. He moved out of the city to upstate New York, then back to Chicago.

There was a final collaboration between Starrett and Abramson. In 1955, Abramson published the recently unearthed script to William Gillette’s curtain raiser, “The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes.” Starrett wrote the introduction to the little booklet.

Abramson died in 1955 at age 56. Starrett recalled him this way:

“With the death of Ben Abramson, July 16, Chicago lost a famous bookman, one who will be missed from the local literary scene in which, for years, he was a colorful and attractive figure. He was a great bookseller and a great personality. His Argus Book Shop was long a mecca of booklovers from other states, and even from abroad.”

The last book of Starrett's work published by Ben Abramson.

The More You Know

- Aunt Matilda is a fictitious relative who showed up periodically in Starrett’s “Books Alive” column and in other essays. As a boy in Toronto, Starrett’s aunts encouraged his reading and early collecting. There was Aunt Lillian and Aunt Bella, but no Aunt Matilda.

- “Calix Meus Inebrians Quam Praeclarus Est” is a portion of the 22nd Psalm and roughly translates as “My cup runneth over.”

- My favorite advertisement on this page is the single line that runs across the top for “Thurston’s Billiard Tables.” See DANC.